REAIE Landscapes of Collaboration: New Possibilities for Education in Complex Times: Reflection Three

July 13, 2025 | Written by Katherine Williams and Tania Lattanzio

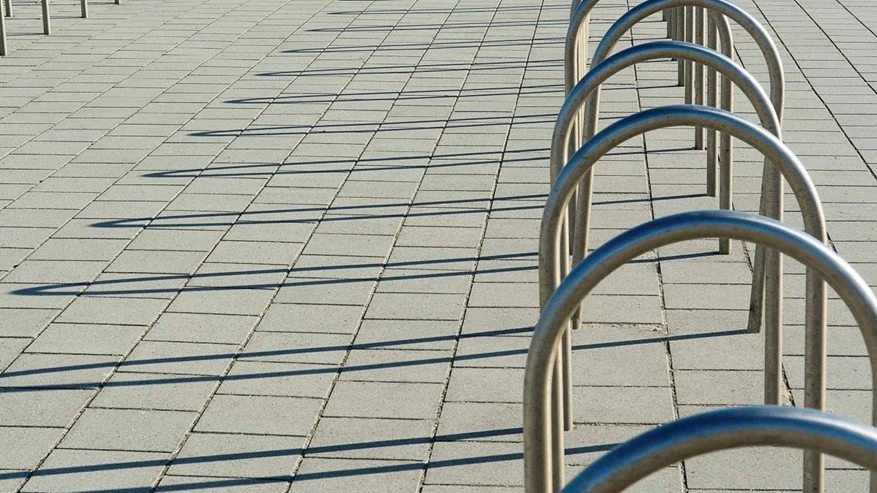

Photo: ...please have a seat! by lichtbankobjekte by M+V As part of the Illuminate Adelaide City Lights

What a joy it was to be part of the Landscapes of Collaboration: New Possibilities for Education in Complex Times conference, hosted by the Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange (REAIE).

These are indeed complex times in education and we are all feeling this in different ways in our different contexts all over the world. Being surrounded by educators so deeply committed to honouring the rights, voices, and potential of children was humbling, inspiring and hopeful. A particular highlight was listening to the powerful words of Consuelo Damasi, atelierista, and Elena Maccaferri, pedagogista, from Reggio Children in Reggio Emilia, so beautifully and respectfully translated by Jane McCall.

This experience served as a powerful reminder of the importance of pausing to reflect, not only on what we do, but on why and how we do it. In the spirit of the Reggio Emilia philosophy, reflection is not an add-on. It is a way of thinking, a way of being, and a powerful tool for transformation.

In that spirit, we will be co-writing a series of blog posts as a way to reflect, learn, grow, and share this experience with others. We hope to capture the richness of what we encountered and the many proposals we are still sitting with.

To be there listening, connecting, participating and engaging in such meaningful dialogue was a true privilege.

Reflection Three: “Embodied Cognition”

In two compelling keynotes “The City at Play: Children Protagonists of the City” by Consuelo Damasi and “The City Grows Like We Do: Conversations and Encounters” by Elena Maccaferri, we are reminded of a fundamental yet often overlooked truth: learning does not reside solely in the brain. It is embodied, relational, and deeply responsive to the environments we inhabit.

Both speakers emphasized the role of adults as researchers, closely observing and learning with children as they explored the city. Children were not led by the adults; they led. They determined the direction, made decisions, and interacted with the city on their own terms, revealing the city as a living, responsive context for inquiry and meaning-making.

Consuelo Damasi invites us to consider how spaces provoke, invite, and respond to children’s attention. When we view children as protagonists - capable, curious, and creative - we begin to see cities not simply as backdrops for learning but as co-constructors of it. She reminds us that “places can act as catalysts for children’s attention.” Consuelo urges us to slow down, to notice how children move through space, invent rules, redefine meaning, and craft intelligent games grounded in emotion, relationship, and cognition. The children were active subjects in the life of the city - bearers and holders of visions manifested in different ways. They walked, interacted with and listened to parts of the city and interrogated what they found. It was “a dialogue between the children and the city”.

“It was as if we were constructing new geographies for ourselves, obtaining a new gaze on our neighbourhood.” The adults and children had lots of encounters on their walks with people who they knew and did not know. There was a dimension of community. When we know people, we feel part of the community. This also connects back to previous points about the importance of participation and dialogue in building our understanding around concepts of belonging, citizenship and democracy.

The theme of play was evident in all the walks. Ways children were inhabiting the spaces were ways of investigating their bodies, balancing on kerbs, climbing on statues, swinging on poles, jumping on and off objects. Children became “serial players”, proposing ideas and transforming the spaces they inhabited through play. They chose paths, altered rhythms, proposed ideas, and navigated their environments with an intentionality that was sensitive, playful and deeply intellectual. They very ably took possession of spaces that were not necessarily designed for them.

Elena Maccaferri builds on this thinking by exploring how children engage with the city as researchers. She reminds us that children “make friends with the space” not only with their minds, but with their whole bodies. This is “embodied cognition” in action. Children don’t just think about their world, they feel it, move through it, and transform it.

Spaces, she explains, are transformed by how children use them, how they “intelligently interpret” them, and how they leave traces of their thinking within them. She shared that children interrogate and interpret architecture through the intelligence of their bodies and their sensibility. They are sensitive to and capable of joking with the spaces. She added that it was quite a different experience and perspective for the children when they explored the city together by walking rather than being pushed around it in a pram or stroller by an adult.

When we truly pay attention, we see that children understand the codes and symbols of the city. They were curious about signs in the street and the adults wondered “What would happen if we let the children design them?”

“How many ways can you get on a bench?” Elena asks. These simple provocations open up profound possibilities about movement, perspective, creativity, and identity. These are not games of distraction, but games of exploration. They are full-bodied inquiries into boundaries, edges, and relationships.

The Role of the Adult

Both keynotes place critical emphasis on how adults accompany children in these inquiries. We are not neutral observers. We are co-learners, researchers, and documenters. Our responsibility is to listen and observe deeply, not just to what children say, but to what they show us with their bodies, with their rhythms, with their silences.

We must craft spaces that are “highly porous” and capable of welcoming “different cultural gazes which interpret and inhabit the cities in different ways”. We must design with intentionality, but also with openness, allowing children to transform spaces through their curiosity, questions and play.

Learning is not just what we know, it is how we move, feel, question, and connect. These keynote reflections from Reggio educators remind us that to truly honour the image of the child, we must honour learning in all its forms: visible and invisible, spoken and gestured, structured and spontaneous.

To quote Loris Malaguzzi “Education is a profession for thinking big.”

As educators, how are we slowing down to see this?

In what ways are the adults making space for opportunities for children to learn and explore with their whole bodies?

How are the adults accompanying the children in their learning?

Katherine Williams and Tania Lattanzio